Sexism and misogyny are rife in the gaming industry. Female gamers often say they have witnessed sexist violence in the gaming world. Nevertheless, it would appear that, depending on the type of game, many men use feminine avatars, for example in MMOs (massively multiplayer online games). However, while the lines between genders are becoming increasingly blurred, gender stereotyping is still very much an issue.

80% of MMO gamers have already used an avatar of the opposite sex, and 30% do so on a regular basis (Martey, Galley, Banks, Wu and Consalvo, 2014). Within this 80% of gamers, there are three times more men than women (Martey, 2015). Video games can be places where players experiment with and subvert their identities, but paradoxically, they offer few or no alternatives to gender stereotypes. To start off this study, we talked to our respective brothers about their real and fictitious identities on social media and in online gaming.

Elie, a 17-year-old high school student, who has been playing MMOs since he was a child, and “Brownich”, (his gamer handle) a 31-year-old former fanatical player of various online games, told us that they both experimented regularly with female avatars, creating and embodying one or a number of them. In order to better understand this recurring phenomenon, we need to examine the main narrative principles associated with female avatars and their representations, if we want to figure out what is really going on when a player consciously chooses to use a female avatar.

“Saving the princess!”: the archetype of the damsel in distress

The representation and character of avatars are charged with meaning and norms, in particular in terms of gender. According to the feminist theorist Judith Butler’s theory of performativity, gender is a social construct. All of our cultural material mirrors our societies and is, as such, loaded with gendered concepts and stereotypes (Butler, 1990). In the history of video games, the rare female characters are often relegated to the role of “damsel in distress”: the character that the main character – generally male – has to save, using his vast skillset and general intrepidness. This normative archetype (Hill Collins, 2011) designates a defenceless being that finds themselves in a dangerous situation requiring the intervention of the hero. This figure is an integral part of our cultural baggage: from the myth of Perseus in ancient times, to the tales of Sleeping Beauty or Snow White, not to mention other, more recent narratives such as King-Kong or Popeye, or the video games of the eighties such as Super Mario Bros, Sonic the Hedgehog and The Legend of Zelda… According to feminist pundit and media blogger

Anita Sarkeesian, who runs feminist frequency, a website that deconstructs the representation of women in the media, video game developers use the damsel in distress trope for marketing reasons. It corresponds to the stereotypes of women as objects and men as fearless rescuers, and as such, is more likely to appeal to video games’ main target market (young boys and straight men, for the most part). One of our study participants, agrees with this concept of fantasy: “For me, the female avatar represents something you want. Content creators are smart enough, in as much as they will attempt to make the hero and heroine sexy, in order to play into gamers’ fantasies. As if you would like to be with the character in a way”. According to Anita Sarkeesian, the powerlessness of the damsel in distress serves to showcase the male character’s skills, depriving her of all agency and any possibility of escaping by herself.

However, the situation is not black and white. This process describes what happens to a female character, and not what it is. The avatar does not always embody this weakness from start to finish. This applies in particular to Princess Zelda, who is described as a powerful character with a range of magic skills who, when required, takes on a more active role, but ultimately always to support the main character in their quest…

“For me, the female avatar represents something you want. Content creators are smart enough, in as much as they will attempt to make the hero and heroine sexy, in order to play into gamers’ fantasies. As if you would like to be with the character in a way”

A super warrior in sexy underwear

Sometimes the female avatar is the main character in the story but, most of the time, it is perceived through what film theorist Laura Mulvey famously referred to as the game designer’s “male gaze”. The “male gaze” tends to exacerbate the character’s sexual desirability and potential to seduce as opposed to their intelligence, agility and bravery, often relegated to the category of secondary characteristics. We should point out that, especially in most war or combat-related games, unlike the armour worn by their male counterparts, the “clothes” the female characters wear are anything but “protective”. Furthermore, as Mona Chollet points out, “The clothes themselves are not the issue, it is the meaning assigned to the clothes and, through them, the role assigned to the character” (Chollet, 2015).

Elie explains it like this: “When I use a girl avatar, I wear what I would like to wear but cannot in real life. Mostly because I would not be comfortable (…) and the clothes are much nicer”. In general, the clothes are flimsy, highlighting areas of the body that are culturally considered to be sexual (breasts, belly, thighs, legs and buttocks). The Street Fighter series provides a good example (among many others), where the female characters often wear very skimpy outfits, even though they are expected to win fights with their bare hands. According to Downs and Smith (2010) after an analysis of 60 popular video games, 41% of female characters analysed are wearing sexually charged outfits, as opposed to 11% of their male counterparts. Furthermore, 25% of female avatars feature unrealistic bodies

as opposed to only 2% of male avatars. In general, research on the subject shows that female avatars are under-represented relative to male avatars, and are often depicted as sex objects (Sarda, 2018). However, the most visible male characters are just as hyper-sexualised, corresponding to idealised codes of masculine virility.

“The clothes themselves are not the issue, it is the meaning assigned to the clothes and, through them, the role assigned to the character”

The female avatar as a mask

Elie explains that “On Moviestarplanet, my very first avatar was a girl, I was copying my older brother. Then, a few years later, I created a boy, and then a girl again when I registered for a VIP account”. Despite the fact that the female characters are, for the most part, perceived to be relatively weak with a limited capacity for action, (exceptions include the Lara Croft character in Tomb Raider for example), it is quite common to see men embody female characters in particular in MMOs. The same goes for Brownich: “My favourite avatar was my female avatar in Guild wars II. To be honest, almost all of my friends chose super-sexy female characters as their first avatar. And then, obviously, you also create male characters but, mostly when you do not have a choice, when the game requires it. For example, when you have to be a warrior or a monk, you cannot be a woman ». After checking, it seems that it is in fact possible to create a warrior or a nun in Guild Wars II. But this statement by Brownich is still interesting and revealing of the supposed gendered status of characters in video games.

« My favourite avatar was my female avatar in Guild wars II. To be honest, almost all of my friends chose super sexy female characters as their first avatar »

According to France Vachey, this trend can be explained by the urge to explore all kinds of feeling and sensations. Creating a female character as a man, or vice versa, allows the player to experience a metamorphosis that goes beyond accepted norms, transgressing the social and physical characteristics that were assigned to them and/or to which they feel they correspond (Vachey, Lignon [dir.], 2015). During the roleplay process, the writer notes that players embody their characters with regularity, sincerity and a pronounced taste for acting, accentuating their avatar’s personalisation and strong identity. It is all about creating a feeling of immersion and appropriation, to play with the limits of one’s identity IRL (“in real life”). However, we should note that some gender limits cannot be overcome: “when you have to be a warrior or a monk, you cannot be a woman”. Each to their own role and the patriarchy is well protected, far from historic reality.

In addition to gender and character, France Vachey also points out that interactions between players also feature a level of gender performativity. The social depiction of gender validates the first impression created by the appearance, while gestures and conversations can either back up the roleplay or can unmask the player, if they do not conform to expectations. Men playing female characters online have to invest in the roleplay to a much greater extent in order to shore up their credibility and avoid damaging or even putting an end to their links to other players. This often means protecting their real-life identity. Brownwich elaborates: “You don’t really ever ask a player for their real identity, unless it is really at an extreme level. When you start to say that you know players IRL, other players understand straight away that there is a strong link between these two players (…). That’s why, for me it is not really that interesting to have an avatar that is like me”.

Does feminine win out over masculine?

“When using a girl avatar, I used to tell other players I was a boy, otherwise guys would send me weird messages. Like, they would ask me for nudes.”

Sociologist Delphine Grellier who studies gender roles in MMOs, tells us that players have a different social experience when they use a female avatar. It would even appear that the choice of gender is a decisive element when it comes to gaming experience: “Players often point out that choosing to embody a female character can constitute a strategic advantage, in as much as other players are more inclined to help them. It is easier to get help, advice, information and assistance, when you are a woman character” (Grellier, 2007). Consequently, being a female character in an MMO is an effective strategy to obtain help from, but also the attention of other players. Furthermore, all of elements that back up the avatar’s gender identity, the clothing and other accessories, confirm the social importance of these gendered appropriations in the game space.

This can also lead to things going off the rails. For example, Elie tells us that using a female avatar as a man can be difficult socially and can lead to sexual harassment. In order to avoid uncomfortable situations: “When using a girl avatar, I used to tell other players I was a boy, otherwise guys would send me weird messages. Like, they would ask me for nudes”. Consequently, embodying and roleplaying as a female does not mean a chance to experiment with new forms of the feminine condition (in the game or IRL) as for the most part, MMOs reproduce a patriarchal schema of behaviour. Vanina Mozziconacci agrees: “Games as a channel come with an extra dose of sexism, an experience that, from a gender perspective, is absolutely in line with the cultural objects they are linked to and the dominant discourse” (Mozziconacci, Lignon [dir.], 2015). Nevertheless, it is important to point out that the super-sexualised avatar is not necessarily the definitive choice, and that things are evolving: each player is free, if the interface for creating avatars allows them, to create their character in the way they choose, without systematically choosing to attribute sexist and unrealistic characteristics. Take Valorant for example (a first-person shooter MMO that dates from 2020), where the game designers made more neutral choices when it came to the options for creating female characters.

The avatar of the future

Consequently, we are faced with a number of paradoxes when it comes to trying to understand what is currently happening with identity in video games. If players were prepared to take their own bias into account, the video game industry could, in theory, provide a laboratory setting for raising awareness and, as such, work as an effective tool for deconstruction (Lignon, 2015). Lignon’s idea is to use the medium to push players to take a critical look at their practices. This could, in the long run, contribute to increased awareness on a global scale. Elie, a Gen Z gamer, seems to be already aware of these issues: “I don’t understand why you need to have long hair and make-up to identify as a woman. For me, the signs that show you identify with the female gender are not linked to the female gender. I don’t really understand how something becomes linked to a gender or not”.

This would allow individual change in our conceptions of what is male and what is female, and on a wider scale, create a shift toward more gender equality. This can only happen if game designers make a wider range of options available (clothing, hair, body types…) that go beyond the cliché of the warrior in sexy underwear.

If the future is actually taking us toward Facebook’s Metaverse, it is time to rethink our vision of gender identity, existing physical codes and sexist norms in order to create a space of equality and respect. When asked the question “If we were to enter the Metaverse right now, would you be a woman or a man?” Brownich answered, “I think I might be asexual!”. What if the new world was in fact pushing us to reinvent ourselves, independent of stereotyped representations of gender?

Butler J., Trouble dans le genre. Le féminisme et la subversion de l’identité, La découverte, 1990/2019

Chollet M., Beauté fatale. Les nouveaux visages d’une aliénation féminine, La découverte, 2015

Downs E., Smith S.L, Keeping abreast of hypersexuality: A video game character content analysis. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 62 (11-12), 2010

Grellier D., « Du joueur au personnage, sexuation des rôles dans les jeux de rôles en ligne massivement multijoueurs », Colloque Genre et transgression : par-delà les injonctions, un défi ?, Université Montpellier III, juin 2007

Hill Collins P., « Get Your Freak On ». Images de la femme noire dans l’Amérique contemporaine », Volume !, 8 : 2, 2011

Lignon F., Genre et jeux vidéo, Presses Universitaires du Midi, 2015

Martey R.M., Stromer-Galley J., Banks J., Wu J., Consalvo M., The strategic female: gender-switching and player behavior in online games, Information Communication and Society, 17 (3), 2014

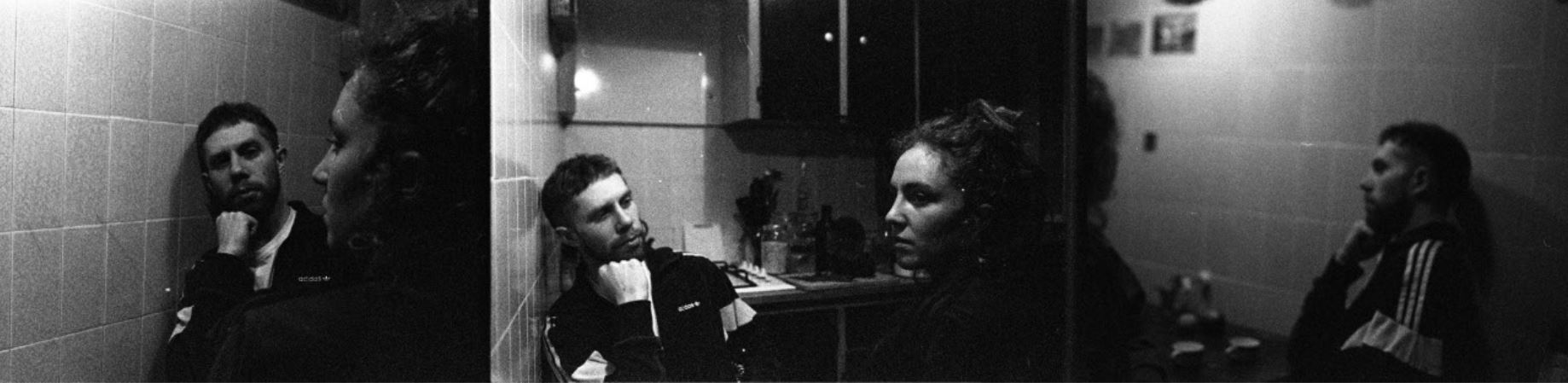

Démarche photographique

Ouvrant l’enquête sur la possibilité de faire muer son identité réelle à partir de celles virtuelles, nous avions, Augustine et moi, toutes deux interrogé nos frères. Malgré la relation intime que nous entretenions avec eux, notre connaissance diffuse de leurs désirs et aspirations, nous n’avions pas remarqué que tout deux alimentaient depuis toujours, dans le secret de leurs chambres, des personnages virtuels féminins. Découvrant les résultats des entretiens, on nous avait rétorqué avec surprise « et ça ne vous fait rien que vos frères se prennent pour vous ?».

A l’image des dialogues avec soi-même au moment de la construction de son identité, les dialogues entre frères et sœurs sont souvent ténus, composé de non-dits et de silences. Le regard porté sur le corps connu depuis toujours est à la fois extérieur et intérieur, impensé et toujours perçu. J’ai photographié des frères et sœurs, à table, espace commun partagé quotidiennement, en les positionnant en miroir l’un pour l’autre. L’appareil photographique tourne autour de ces présences comme autour d’un volume, pour approcher l’altérité de l’un dans sa ressemblance à l’autre.

L’enquête s’approfondit et nous constatons qu’ils sont plusieurs garçons à partager cette pratique, à silencieusement imaginer leur double féminin.