The dating app Tinder treats “emotions as commodities”, according to sociologist Eva Illouz1, encouraging users to standardise their profiles. The user must depict themselves in the most attractive and original light possible, using only a few photos and a short presentation as their profile is judged in a matter of seconds. These codes tend to restrict the options available to tell one’s story.

“It is such a strict, rule-bound way of representing yourself that I really like it when someone obviously doesn’t take it seriously. It’s like a breath of fresh air inside a slightly robotic set- up”, says Audrey*, a 23-year-old photography student about the profiles she comes across on Tinder.

Tinder is one of the most popular dating apps in the world but the way its algorithms are designed encourages users to standardise their profiles.

The user is required to open an account indicating their interests, job and education, gender, and sexual orientation. The profile is filled out with just a few photos and a few words, chosen and written by the user. Presentation is key to getting as many ‘likes’ and ‘matches’ as possible (when two people mutually ‘like’ each other’s profiles), in order to be able to connect with other users.

Most users spend mere seconds judging the profiles they see, and you cannot even be sure they will look at all of the photos. Telling your story on a platform that is restrictive and competitive is indeed a challenge.

Men go for sports and animal shots while women go for beaches and cocktails

We spoke with a number of people in their twenties to get their perspective on the interface. Even though their expectations are not particularly high to begin with, they find it boring, as the app’s extremely standardised settings make most profiles blur together.

Marie, a 22-year-old student, tells us that most men’s profiles show photos of sport, an animal, a musical instrument, or a holiday. Aurélien, a 23-year-old lighting engineer, mentions girls wearing “little dresses, and make-up”, while Audrey and Camille, who both date women, spoke of “beach and cocktail” photos. Another interviewee, Nina, says she has the impression that the profiles are increasingly stereotyped: “You can even tell what school someone went to, after a while, you can guess what school they go to or the subjects they study. For example, I get a lot of Sciences Po Paris students, and they all introduce themselves in the same ‘cool kid’ way, with a funny comment etc.”

Sociologist Marie Bergstöm’s research2 shows that practices and codes differ depending on the social and cultural origins of the users and that users from more privileged backgrounds tend to go to great lengths to create a feeling of spontaneity. This gives the impression that the user is detached from the app as if Tinder is not something to be taken seriously. This is reflected in our interviews with the photography students we spoke to, like Camille, who would not use professional or artistic photos to avoid seeming “too much”.

Low-key or filtered photos: social background markers

According to Marie Bergström, profiles of users from less privileged backgrounds tend to be more functional. Users look straight to camera with a little smile or use a selfie or screen grab from their Snapchat account (a photo-sharing app). These photographic formats are rare among users with a higher level of education. A 22-year-old art history student admits “If I look at a profile, I can see straight if the photo is low-key and understated, or, on the other hand, if there are filters or texts on it: very often the latter will be someone who has not had a third level education, or something I don’t relate to, and we will not have much to say to one another”. Marie Bergström notes that photographs are chosen based on “extremely biased, snap judgments related to social status”.

Users are harsh critics of the way people present themselves in the profiles they scan. They integrate Tinder’s presentation constraints very quickly. If a user wishes to stand out, they need to create an original presentation, in the hopes that it will get a reaction.

Compose yourself !

Tell your story in five pictures

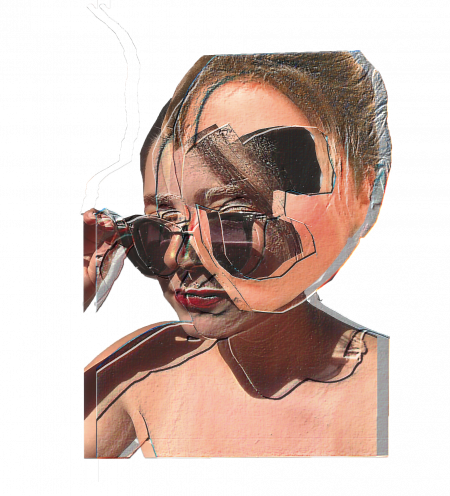

Among the people we talked to who had given their photo choice some thought in terms of what they are projecting about themselves, a number of options emerged. Camille, 21 years old and non-binary, limits the amount of information they provide. Their strategy creates a feeling of suspense and an urge to see the next photo, shot from a different angle, as they reveal themselves a little more each time: “I start with a photo where you can’t really see my face […], you have to shift a little to try to see more”. They say they are trying to reproduce what happens in real life, offline, where the process of seduction means people reveal themselves gradually.

Audrey, 23, on the other hand, prefers to depict herself as fully as possible by choosing a diverse range of images. She feels it is important to use a photo for each part of her personality, that way, other users know what to expect. “People can pick through what they like and who they like”, which makes sorting through the thousands of accounts on the platform a little easier. If the photos are representative of the person, it makes it easier to pre-select a certain type. In the same way, she makes the effort to provide full-length photos from a few different angles, to avoid being guilty of “fraud”.

Marie and Nina, two young women in their twenties from the suburbs just west of Paris, agreed to show us an initial selection of five photos that tell their stories, with no ulterior motive to seduce. Then, they made a similar selection, but this time, for a Tinder profile. At a glance, we can tell that, in the first case, their narrative tends to include old family photos, photos they took themselves and that they are rarely alone. In the second case, they become the central figure, they feature in every photo, most often alone or very distinctly separate from the others. Introducing yourself on Tinder means, first and foremost, displaying your physical characteristics.

The risk of self-deprecation

Among the swarm of candidates, those we interviewed confirmed that very few people choose to post photos where they themselves are not present. Those that do, often post funny pictures or memes. This raises the question of choosing to use humour or irony in a profile. Audrey, Camille, and Marie have all come across profiles that do not show any portraits. No one we spoke to uses memes: a photo where they are laughing usually suffices. Camille explains that “self-deprecation is a deal-breaker for some people”. She admits that it’s fun, but for her, fun comes on a second date.

“You know, wanting to stand out is a real choice, wanting to be original”, they point out. Going down the humour, self-deprecating route to stand out from other profiles means you run the risk of seeming too detached from the process: “I find profiles like that funny, but I won’t often “like” them because you get the feeling that they are not taking it seriously”, says Marie. If the order of the photos is not an issue for the user, they can activate the “smart photos” option, so the app can highlight the one that is likely to be most popular with other users.

Tinder elo score, points for desirability

Presentation choices on Tinder are not without consequences on the way the app works. It uses a sophisticated algorithm that presents the user with profiles that correspond to the users’ criteria, and if you live in a big city, like the students we spoke to, you are presented with hundreds of profiles. Swiping can become compulsive and almost addictive, something to relieve the boredom of commuting for Gaspard, or to fill a gap at work when avoiding a particular task for Marie. Everyone agrees that what makes them go back to Tinder is their need for an ego boost: even if most matches go nowhere, it’s still nice to know that someone likes you.

The algorithm will even – for a while at least – give you updates on how well your profile is working, thanks to your “elo score”, in other words, your desirability grade. This score is calculated according to your level of popularity and number of matches. On reading Judith Duportail’s book Amour sous algorithme, Journalist Michaël Szadkowski 3 reports that “This implies that the Tinder profiles presented to the user would differ according to their elo score in order to encourage matches between users who get the same score”.

A vicious spiral that can even go as far as harassment

The app plays on the shift from hot to cold, from the ego boost of a good match to the frustration of not getting any, thus creating an addiction. An article in Le Monde explains that “About 20% of male users correspond to certain criteria and get a huge amount of matches. The other 80% of men and all the women on the app are stuck in a vicious spiral that can lead to frustration, aggressivity and harassment”, it goes on to say that “On Tinder, men and women move in parallel worlds” 4 . Frustration and addiction are the two factors that push users to buy subscriptions from Tinder and raise their chances of success (mainly male users, cf. “La recette très secrète de Tinder (Tinder’s very secret recipe)” Le Monde 3 ). None of the people we talked to pay a subscription to the app, except through the advertising on the interface.

“Emotions as commodities” are inexhaustible and can be consumed over and over. This notion was developed by Eva Illouz 1 , in her book Les marchandises émotionnelles : l’authenticité au temps du capitalisme (2019). In the seventies, the commodities market became saturated so a “commodity developed that was inexhaustible and could be consumed over and over again”, the urge to “build oneself” and “the culture of personal development with the aim of attaining a state of well-being that is never reached”, which is, according to the sociologist “a huge market!”. This was followed by the creation of “new social castes based on happiness and positivity […] that consisted of grading people according to their good humour, and the level of happiness capital that they could bring to the workplace”: a grading system that is not unlike the practices of dating apps.

Society and individuals are attached to love and what it should be: sacred. Eva Illouz goes on to say that “Algorithms and social norms are not supposed to apply to love”, which goes against the portrait of Tinder we have painted in this article. The business of the app is based on a search for love/ sex and on what Illouz refers to as “emotions as commodities”.

* the first names have been changed

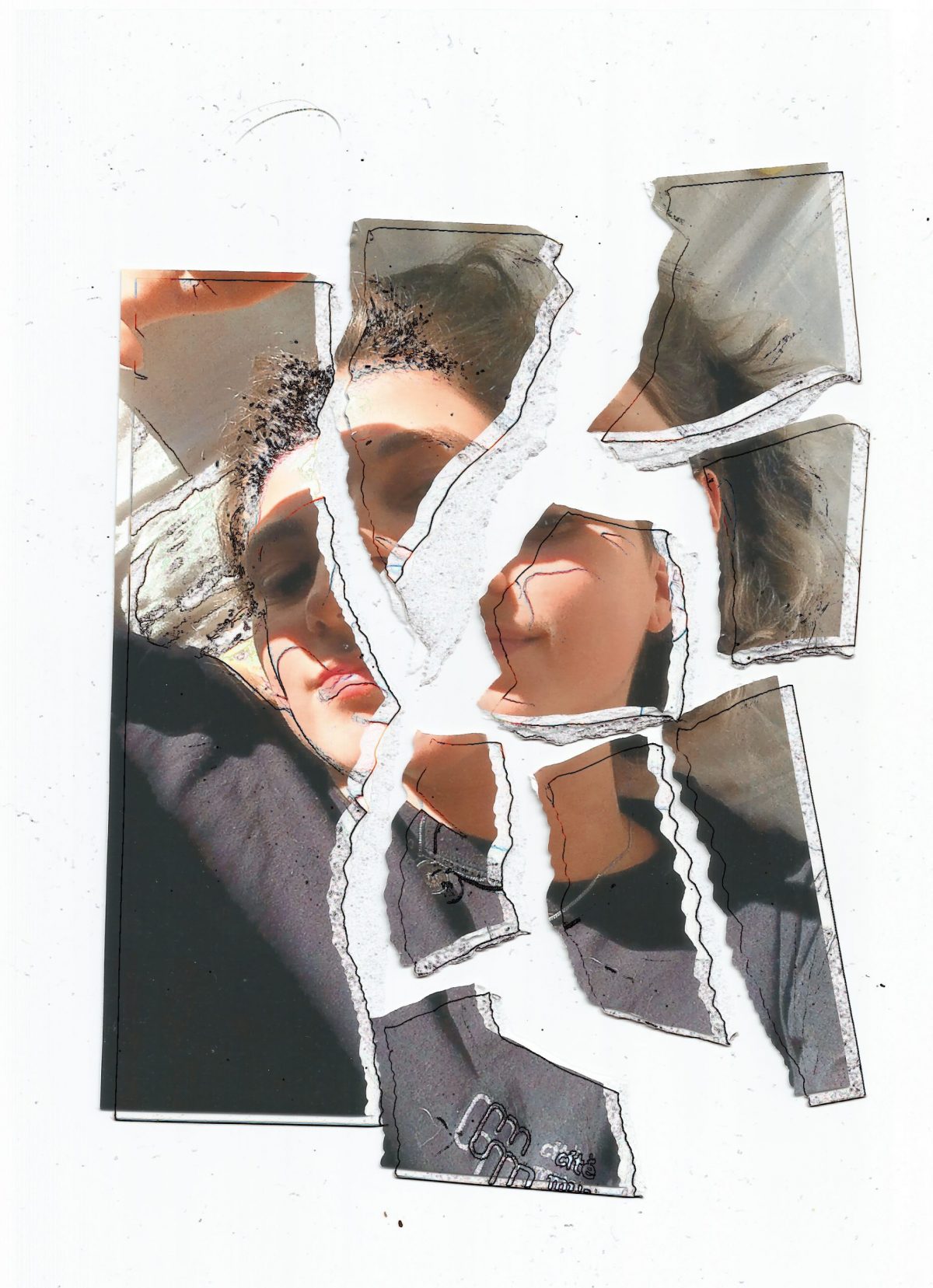

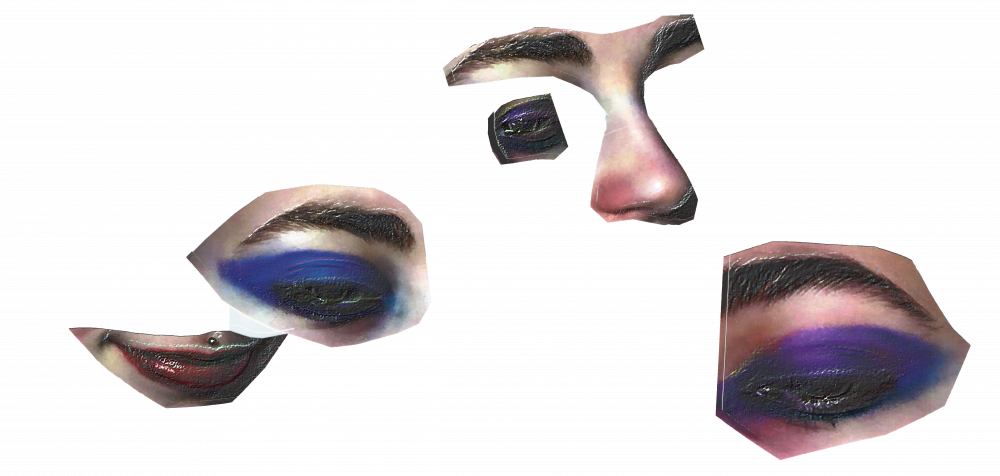

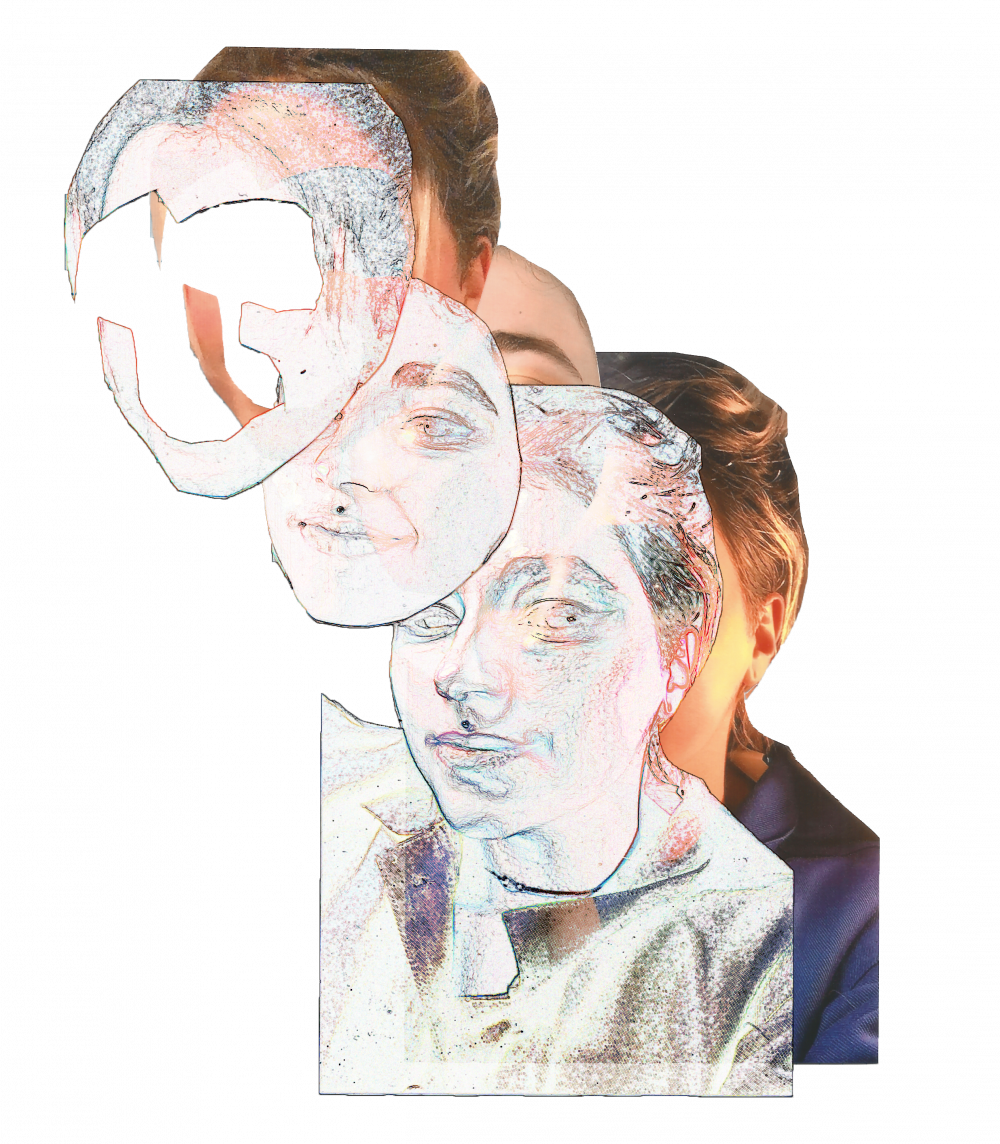

On Tinder, people represent themselves in only a few pictures. This limited showcase fores users to fragment themselves. Like a cadavre exquis, they choose, cut, past and redfine themselves in a digital world. Do these collected, often intimate pieces truly reflect us? In the end, who are we through what we decide to show or, who do we decide to be?

1. France Inter. Eva Illouz : « L’émotion est un champ particulièrement important pour le capitalisme (Emotions provide a huge market for capitalism)», April 11, 2019. Consulted on December 7 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b3JvyhEImIE

2. « Marie Bergström : Sexualité, couples et rencontres au temps du numérique — Sciences économiques et sociales (Marie Bergström: Sexuality, couples and dating in the digital age — Economic and Social Sciences) », February 2020. Consulted December 9 2020. http://ses.ens-lyon.fr/articles/marie-bergstrom-sexualite-couples-et-rencontres-au-temps-du-numerique#section-0

3. « La recette très secrète de Tinder ». Le Monde.fr, March 28 2019. https://www.lemonde.fr/pixels/article/2019/03/28/la-recette-tres-secrete-de-tinder_5442513_4408996.html

4. « Sur Tinder, les hommes et les femmes évoluent dans des mondes parallèles ». Le Monde.fr, July 26 2019. Consulted November 30 2020. https://www.lemonde.fr/pixels/article/2019/07/26/sur-tinder-les-hommes-et-les-femmes-evoluent-dans-des-mondes-paralleles_5493933_4408996.html